"Anicca" Matte Poster (unframed)

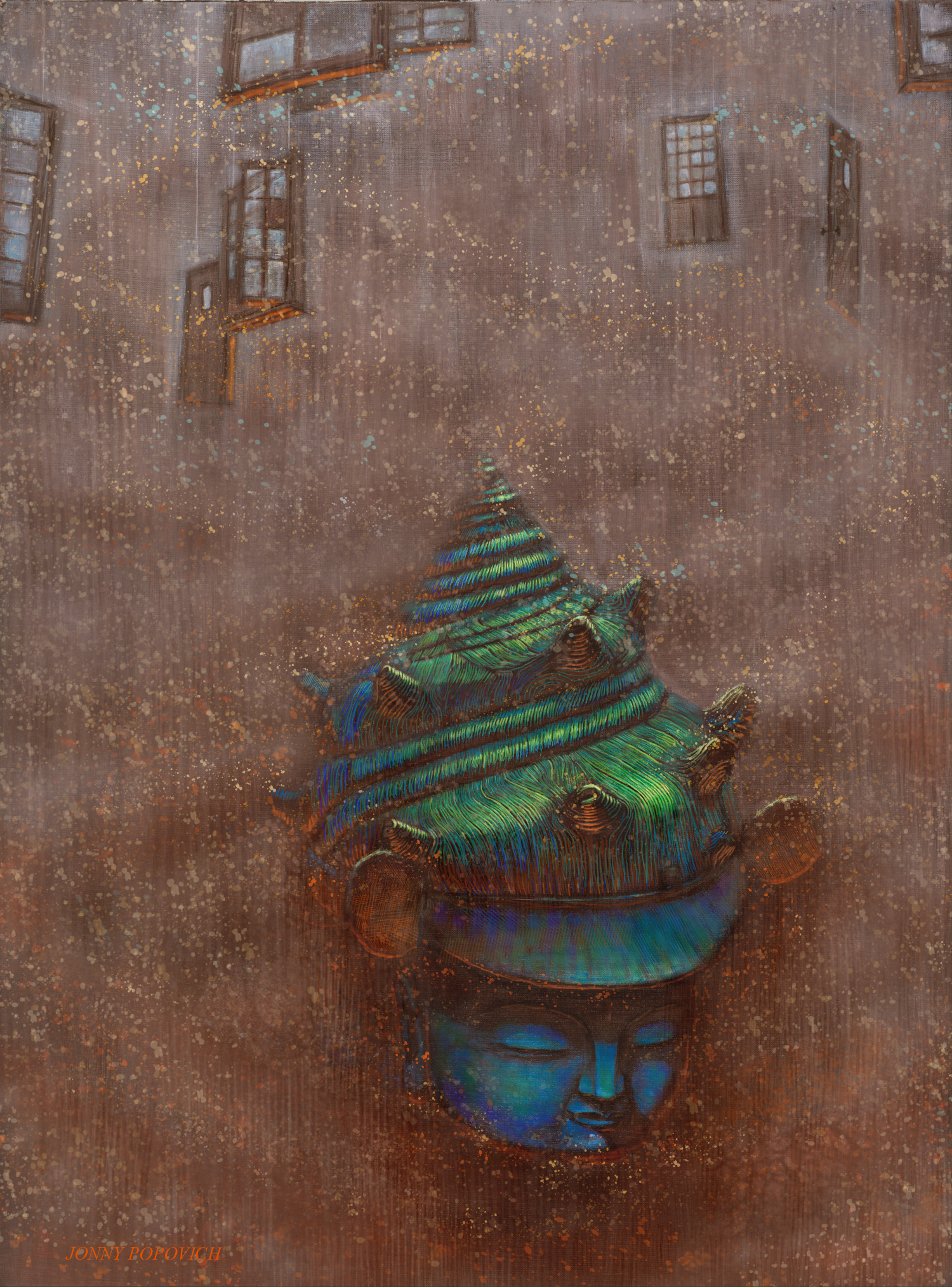

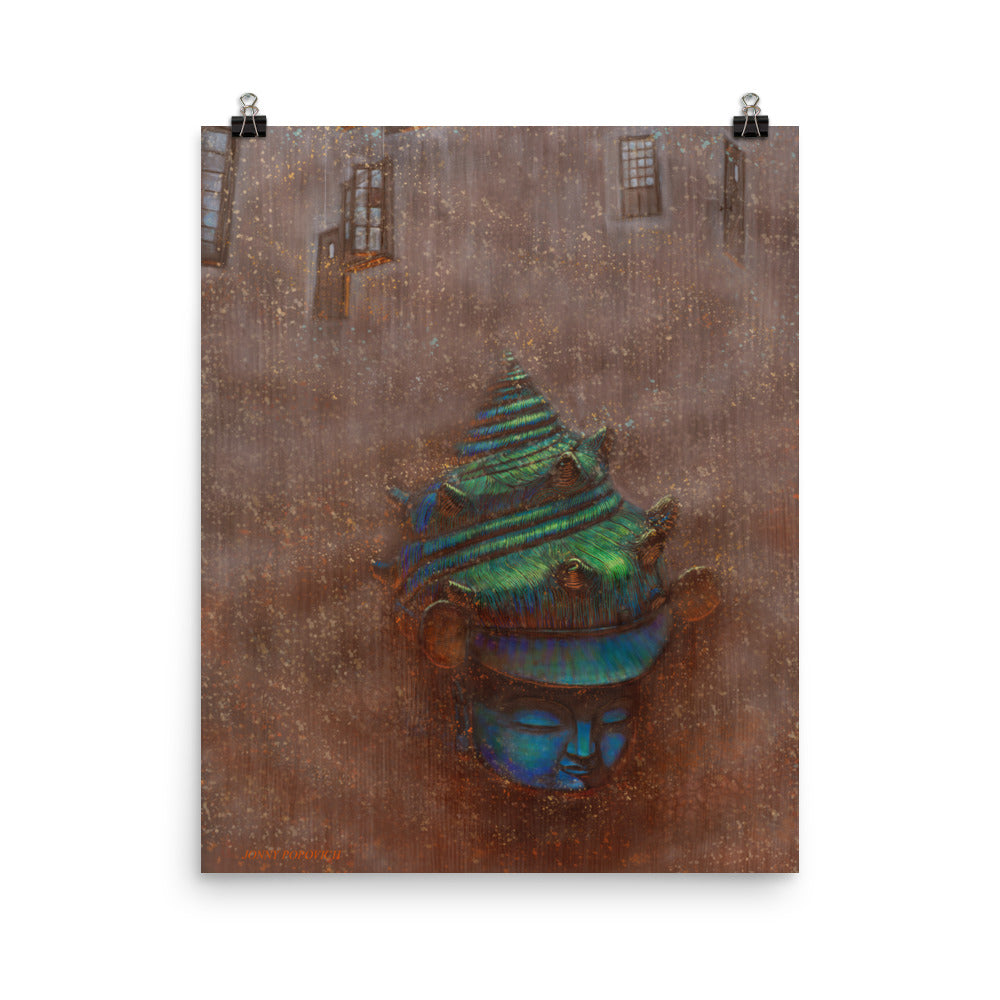

The subject matter in this piece are things I saw in Japan during my travels: an installation of “collaged” house parts suspended in midair on the enchanting island of Inujima, a shell-type samurai helmet from the 16th century seen at Osaka castle, and an omnipresent Buddha face. Japan was the first place I landed to kick off my 19-month-long odyssey across much of the globe. It was a dazzling, whirlwind month full of mesmerizing art, unrivaled food, and steady adventure. When I landed in Brisbane, Australia, after leaving Japan, I did not want to be there. I wanted to stay in Japan and respond to my experiences through art. So in Brisbane I reached out to a local gallery and basically asked for a space to paint in exchange for whatever volunteer services they might need. I noted my height and long arms, and Pete, the director there, agreed that at least my limbs might be of some use.

This painting marks the genesis of my current color palette. This is where I first explored the vibrant blue-greens against a warm brownish background. I’ve fallen in love with that aesthetic and expanded it, especially in the murals I’ve since painted. Together the elements in this painting create the mood I like to depict in my surreal works, which is a kind of tranquility or placidity depicted through serene countenances, floating objects, and a glowing airiness. What I am ultimately interested in, though, is color, form, composition, light, edges, and the emotional impact induced by their relationships. I want to construct a clear sense of form, volume, structure, space and I want to make something beautiful. The facial expression serves to generally dictate the emotional constitution, and the conch shell, with its roughly parallel, winding striations, highly similar to the trees I paint, exemplifies the forms I love to render. Temperature difference between colors is crucial to the impact of the piece because, in this case, the warm substrate creates the glowing, permeable airiness I strive for, while the cool, opaque greens and blues create a contrasting distinction of solid form.

Down the road, months and years after completing this piece, it’s content has taken on new meaning amidst other travels and experiences. When I was in Nepal, two Nepali wood carvers mentioned that the spiralizing conch helmet mimics the climb toward enlightenment that Buddha’s twisting hair beads traditionally symbolize. They added that, to them, the windows and doors symbolized being open to this path of enlightenment. I also think of the doors and windows as representing the various channels through which we experience stimuli, including thoughts themselves, and their corresponding physical sensations, which, according to my understanding, subsequently trigger our habituated reactions, which then give rise to our ingrained emotional states. This is a crucial insight to understanding what generates our emotional and mental habit patterns.

Around the same time I was reading the popular book Sapiens, by Yuval Harari, who writes, “For the last 2,500 years, Buddhism has assigned the question of happiness more importance than perhaps any other human creed. The problem, according to Buddhism, is that our feelings are no more than fleeting vibrations, changing every moment, like the ocean waves. If five minutes ago I felt joyful and purposeful, now those feelings are gone, and I might well feel sad and dejected. Why struggle so hard to obtain such ephemeral prizes? The real root of suffering is this never-ending and pointless pursuit of ephemeral feelings, which causes us to be in a constant state of tension, restlessness and dissatisfaction.” While you may be generally familiar with such principles on an intellectual level, truly understanding this concept at the experiential level and therefore actually benefitting from it takes dedicated practice, and can seem impossible to maintain for more than moments at a time.

A couple years after painting this, I have done my first Vipassana meditation retreat, a 10-day silent course, purportedly developed and taught by the Buddha, again imbuing this piece with new meaning. That is where the title comes from. Anicca (pronounced “ah-nee-cha) is the Pali (ancient Indian language) word for impermanence, describing the ephemeral nature of all states of mind and body, no matter how compelling they may be in the moment. It was drilled into us like a mantra during each sitting. The ultimate goal is to maintain awareness, from moment to moment, ideally at all times, of bodily sensations, coupled with unwavering equanimity, thus liberating one from the suffering of wanting to alter such states, either through craving or aversion. I maintained about 1.5 hours of vipassana practice for about two weeks following my retreat. Now I’m delusional 99% of the time once again.

These matte, museum-quality posters are printed on durable, archival paper.

This painting marks the genesis of my current color palette. This is where I first explored the vibrant blue-greens against a warm brownish background. I’ve fallen in love with that aesthetic and expanded it, especially in the murals I’ve since painted. Together the elements in this painting create the mood I like to depict in my surreal works, which is a kind of tranquility or placidity depicted through serene countenances, floating objects, and a glowing airiness. What I am ultimately interested in, though, is color, form, composition, light, edges, and the emotional impact induced by their relationships. I want to construct a clear sense of form, volume, structure, space and I want to make something beautiful. The facial expression serves to generally dictate the emotional constitution, and the conch shell, with its roughly parallel, winding striations, highly similar to the trees I paint, exemplifies the forms I love to render. Temperature difference between colors is crucial to the impact of the piece because, in this case, the warm substrate creates the glowing, permeable airiness I strive for, while the cool, opaque greens and blues create a contrasting distinction of solid form.

Down the road, months and years after completing this piece, it’s content has taken on new meaning amidst other travels and experiences. When I was in Nepal, two Nepali wood carvers mentioned that the spiralizing conch helmet mimics the climb toward enlightenment that Buddha’s twisting hair beads traditionally symbolize. They added that, to them, the windows and doors symbolized being open to this path of enlightenment. I also think of the doors and windows as representing the various channels through which we experience stimuli, including thoughts themselves, and their corresponding physical sensations, which, according to my understanding, subsequently trigger our habituated reactions, which then give rise to our ingrained emotional states. This is a crucial insight to understanding what generates our emotional and mental habit patterns.

Around the same time I was reading the popular book Sapiens, by Yuval Harari, who writes, “For the last 2,500 years, Buddhism has assigned the question of happiness more importance than perhaps any other human creed. The problem, according to Buddhism, is that our feelings are no more than fleeting vibrations, changing every moment, like the ocean waves. If five minutes ago I felt joyful and purposeful, now those feelings are gone, and I might well feel sad and dejected. Why struggle so hard to obtain such ephemeral prizes? The real root of suffering is this never-ending and pointless pursuit of ephemeral feelings, which causes us to be in a constant state of tension, restlessness and dissatisfaction.” While you may be generally familiar with such principles on an intellectual level, truly understanding this concept at the experiential level and therefore actually benefitting from it takes dedicated practice, and can seem impossible to maintain for more than moments at a time.

A couple years after painting this, I have done my first Vipassana meditation retreat, a 10-day silent course, purportedly developed and taught by the Buddha, again imbuing this piece with new meaning. That is where the title comes from. Anicca (pronounced “ah-nee-cha) is the Pali (ancient Indian language) word for impermanence, describing the ephemeral nature of all states of mind and body, no matter how compelling they may be in the moment. It was drilled into us like a mantra during each sitting. The ultimate goal is to maintain awareness, from moment to moment, ideally at all times, of bodily sensations, coupled with unwavering equanimity, thus liberating one from the suffering of wanting to alter such states, either through craving or aversion. I maintained about 1.5 hours of vipassana practice for about two weeks following my retreat. Now I’m delusional 99% of the time once again.

These matte, museum-quality posters are printed on durable, archival paper.